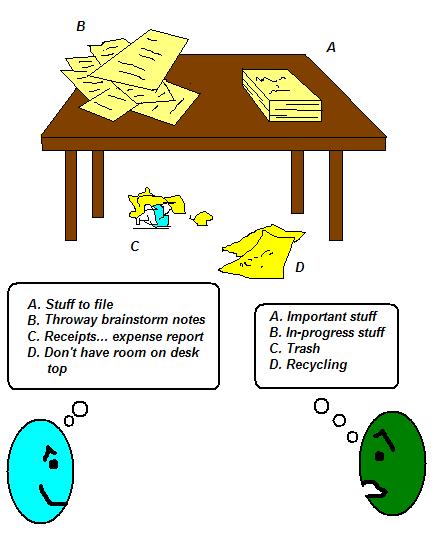

I had one of those “why didn’t I make the connection before? It’s so obvious!” moments recently, while thinking through a chapter of my book-in-progress. The three things I connected were David Allen’s subtle definition of organization: “where things are suits what they mean to you,” James C. Scott’s masterpiece on how governments develop an organizational “view” of reality, Seeing Like a State, and Gareth Morgan’s magisterial work on the role of metaphor in organization theory, Images of Organization. Why is this of interest to us? Well it turns out, if you put these three things together, you can explain why and how neatness and organization differ. You can also explain why it is so much harder for groups to get organized, compared to individuals, why they end up neat rather than actually organized, and what to do about it. Let’s start with this picture:

Legibility, Other-Meaningfulness and a GTD Definition of Neatness

In the classic GTD paradigm, you cannot objectively state whether this desk is organized or not. It depends on what the arrangement of stuff in this workspace means to the the owner, Blue Head guy. It is definitely not neat, but this could count as perfectly organized, if Blue Head routinely dumps his receipts under the table after a trip, and uses the floor when he needs extra workspace. If he gets his expense reports done on time, and never loses stuff on the floor, who are you and I to judge? When I was a graduate student at the University of Michigan, I saw a fine example of this. My thesis adviser was a neat and organized guy. Nothing was ever out of place. Things got processed, and his desk surface was always immaculate. Across the hall at the time was another professor, for whom I was a teaching assistant one term. His office looked like a huge mess. Piles of journals and papers were everywhere. If you dropped by, there would be nowhere to sit. Yet, he could find what he needed in seconds. Both were equally effective and productive as academics. I realized that the second professor was very self-aware and actually understood his system at a philosophical level when I found a copy of Malcolm Gladwell’s article “The Social Life of Paper” clipped to his door (a very smart exploration of how people really use paper to organize).

But to understand what “neatness” is, consider what someone else makes of an organized-but-not-neat situation, like our friend Green Head in the picture above. Why does he come to the different set of conclusions about what the four groups of “stuff” mean?

The deep reason for this is the association of neatness with low entropy. In the non-living world, symmetry, straight lines, right angles and such are only created by humans (or by atomic forces at microscopic crystalline levels). The result is that if you don’t know anything else, you can always safely assume that these attributes represent meaning to somebody. So even without knowing what the pile A means to Blue Head, Green Head can guess that it probably manifests some meaning.

Now, let’s mix in Scott’s notion of “legibility.” Scott argues that organizations tend to take complex realities created by organic human societies and reconstruct them in “neater” ways simply to make them easier to see and control organizationally. This process by which governance systems try to make the governed more “legible,” he goes on to show, often backfires by getting rid of a lot of critical subtleties in meaning, simply because they are not easily made legible. This reductive view of a rich reality is then imposed by the governance system onto the reality itself, as a Procrustean bed. The result is a mess; a case of an attempt at organization breaking what didn’t need fixing. A beautiful example he discusses is how the imposition of the more legible and “standardized” metric system in Napoleanic France actually made land measurements for the purpose of taxation less accurate in some cases.

That notion of legibility gives us a definition of neatness that is a companion to David’s definition of organization.

Neatness is that property of stuff that makes it legible to people other than the owner of that stuff.

Neatness, in this sense depends only on the stuff itself, not on the relationship between Blue Head and Green Head, or the extent to which they share a sense of meaning. Green Head could be an alien for all we care. That’s what legibility means: stuff in another language can be judged for legibility whether or not you can parse its meaning. You don’t need to know Chinese to tell random doodles made by a Chinese kid from written language, or good calligraphy from bad. The same goes for each of our private “languages” of organization.

But if, in addition (or instead), Blue Head and Green Head have shared meaning — shared mental models of some commonly experienced part of the universe — the desk will be more than legible to Green Head. it will be other-meaningful. It can even be illegible and still be other-meaningful to specific “others.” Here are a few examples, ranging from the “naturally self-documenting and legible” and “legible and consciously documented” to “meaningful but illegible” and the stupidest variety: other-meaningful and legible but not meaningful to the owner.

Examples of Meaning, Other-Meaning and Legibility

- I once saw a short-order cook taking omelet orders. His system was transparent, meaningful, legible and other-meaningful. If someone ordered an onion, tomato and swiss cheese omelet, he’d queue up a plate on the counter with a small piece of tomato, a small piece of onion, and a slice of swiss cheese. It was instantly obvious to anybody looking how his kitchen was organized.

- A pair of unlabeled paper trays on a desk is legible but not other-meaningful. “In” and “out” labels make them “other-meaningful.”

- A hook by the front door is legible and has a clear meaning and other-meaning: hang your keys there

- Sherlock Holmes stored his tobacco in a Persian slipper which he hung by the fireplace. Legible and other-meaningful. Nobody can accidentally create that weird configuration of stuff. It conveys: “smoker, eccentric, this is where he keeps his tobacco” as its other-meaning.

- The crumpled receipts and sheets of paper under the desk in the picture are not legible. A zealous janitor could be forgiven for trashing pile C and shredding pile D. If he’s been told to leave the desk area alone, it will acquire some coarse other-meaning for him (“not trash even if it looks like it”).

- Couples frequently get into fights over legibility and other-meaningfulness. My wife used to keep some clothes draped over the edge of the laundry hamper, and occasionally, annoyed by the entropy, I’d dump it in fully. Until I realized “draped over edge” meant “to dry clean” to her, and I was destroying her meaning by making things neater and other-meaningful to me.

- Moving time is a great example of various forms of meaning and legibility. There are piles of stuff are everywhere, but you and your spouse know exactly what it all means, even if the neighbors don’t. On the other hand, to a trained observer, such as a mover, who has seen lots of moves, things can be more legible and other-meaningful than the owners expect. Perhaps a psychologist or GTD coach would read more other-meaning into the moving piles than the couple themselves can!

- A contrived example of individual humans “seeing like a state.” Imagine a well-meaning but terminally stupid new admin assistant taking a look at an executive’s illegible but meaningful workspace. In particular, this executive has an elaborate system of post-it notes pasted in groups around his desk and monitor. The notes are different colored, but the executive isn’t using the color to code anything. Our overzealous admin imposes a moronic new other-meaning onto the executive’s workspace by neatly rearranging all post-it notes by color, in neat rectangular arrays. You can imagine what would happen when the executive returns to his office.

Personally, I am pretty much always organized, but my neatness swings between illegible and highly-legible. When legible, my systems are not very other-meaningful beyond “this isn’t trash, so don’t mess with it.” I don’t document much.

Creating Shared Meaning

This suggests a rather depressing thought: one of the reasons you and I are attracted to GTD is that it is not just tolerant of personal idiosyncracies, it actually encourages hacking and customization and apparent creative anarchy, so long as the “meaning” criterion is respected. But what happens when you must collaborate and coordinate with others? Is neatness and objective legibility the only path to other-meaningfulness? Is “seeing like a state” an unavoidable pathology?

Fortunately, no. You can create collaborate beautifully without getting into neatness. The key is to get to agreement on what stuff means, rather than how it should look. Crazy-creative startups have such deep levels of shared meaning that they can be phenomenally well-organized but completely illegible to visitors from big corporations. In the other direction, we instantly recognize “petty bureaucracy”: big-organization stuff that is neat and legible, but meaningless and other-meaningless because the process was designed under conditions that no longer exist, for and by employees who are no longer around to explain.

And here’s where the third piece of the puzzle comes in: organizational metaphor. Since the degree to which you need to share meaning is the degree to which others’ systems need to be legible and other-meaningful to you, smaller groups can create shared meaning in more fluid ways than bigger groups. But even the biggest organizations can create shared meaning that goes a really long way without degenerating into “Seeing Like a State” disorganized neatness.

This level of shared meaning is created by your fundamental metaphor for your organization. Morgan analyzes several major ones in his book. I have listed them here.

- Organizations as machines

- Organizations as organisms

- Organizations as brains

- Organizations as cultures

- Organizations as political systems

- Organizations as psychic prisons

- Organizations as flux and transformation

- Organizations as instruments of domination

Not all these metaphors impact visible systems and processes equally, but if you can read the dominant metaphor, the entire organization will become a lot more legible and/or other-meaningful to you. A simple example: if everyone seems to dress casually, and there are always cookies and fun posters around, you can probably assume that the ‘culture’ metaphor is important, and that it reads ‘fun and relaxed.’ You can use that to deduce that an illegible desk, that might mean “disorganized and ineffective” in a true “machine” organization, probably means the opposite here. If you know that an organization has a lot of the “brain” metaphor going on, where people get things done by acting like neurons — communicating intensely and informally at the watercooler — then you can read that behavior as “effective” instead of “disorganized slacking off.”

There isn’t room here to go into this in detail, but this view of organization, neatness, legibility and meaning is a very powerful way to look at effectiveness in decision-making. If you’d like to explore this theme more, the two books are well worth checking out. I must warn you though, they are heavy-lift books. Don’t expect to knock either off on a single plane ride. And of course, my own in-progress book, Tempo, a book about decision-making, will have a whole chapter devoted to the theory and concepts behind this approach to analysis. Do visit that link and sign up for the release announcement if this subject interests you!

p.s. I will be participating in two of the panels at the GTD Summit, where I’ll share some more ideas from my book, as they relate to GTD! Do drop by if you plan on being there.

Venkatesh G. Rao writes a blog on business and innovation at www.ribbonfarm.com, and is a Web technology researcher at Xerox. The views expressed in this blog are his personal ones and do not represent the views of his employer.

Immensely instructive post! Very rare, too, in value, because it’s actually NON, yes NON-prescriptive!

You deliver food for thought–not 7, not 11 or 17 commandments, rules, laws or whatever other edicts. This is the very best kind of writing. I look forward to your book.

Now to check out your other book recommendations.

Great job. Appreciate your effort.

bob

Dear Venkat,

Valuable and instructive! Neatness is an affliction & entropy at the same time :). You have brought in the ‘other meaning’ edifice that is thoughtful and conveys immense insight!

Looking forward to your book.

Regards,

Manju